The Supreme Court is set to consider Trump's claim to immunity in a case involving election interference.

No president has ever been criminally indicted while in office or after leaving office.

The Supreme Court is closely watching the case of former President Donald Trump, who has presented a broad argument for why he should not be tried for alleged election interference.

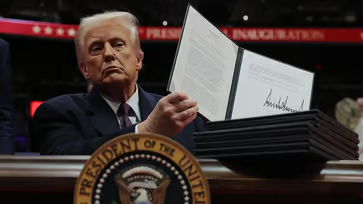

The high court will hear arguments on Thursday morning that could impact the former president's personal and political future. As the presumptive GOP nominee, Trump hopes that his constitutional claims will result in a legal respite from the court's 6-3 conservative majority, with three of its members appointed by the defendant himself.

Will a former president be granted immunity from criminal prosecution for actions committed while in office, and to what extent?

No previous president has been criminally indicted, making this new ground for the Supreme Court and the country.

The stakes are high for both the immediate election prospects and the long-term impact on the presidency and rule of law, as the Supreme Court will hear a case directly involving the former president for the second time this term.

On March 4, the justices ruled unanimously that Trump could remain on the Colorado primary ballot despite allegations of insurrection in the January 6, 2021 Capitol riots.

The decision to intervene in the immunity dispute at this stage is a mixed bag for both Trump and the Special Counsel. While the defendant wanted to delay the process indefinitely, Jack Smith wanted the high court appeal dismissed immediately to expedite the trial process.

A federal appeals court had unanimously ruled against Trump on the immunity question.

"The three-judge panel ruled that, for the purpose of this criminal case, former President Trump is now considered a citizen, with the same defenses as any other criminal defendant. However, any executive immunity that protected him while he was President no longer shields him from this prosecution."

THE ARGUMENTS

The former president has been accused by Smith of conspiracy to defraud the U.S., conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding, obstruction of and attempt to obstruct an official proceeding, and conspiracy against rights.

The charges against Smith were a result of his investigation into Trump's alleged plot to overturn the 2020 election result, which involved participating in a scheme to disrupt the electoral vote count, ultimately leading to the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riot.

Trump pleaded not guilty to all charges in August.

In its brief on the merits submitted this month, the Special Counsel informed the high court that "presidents are not immune to the law."

The government stated that no former President has ever been granted criminal immunity by the Framers, and all Presidents, from the founding to the present day, have understood that they may face criminal liability for their official actions after leaving office.

Trump's legal team argued in the high court that denying him criminal immunity would render every future president vulnerable to blackmail and extortion, and subject them to years of post-office trauma at the hands of political opponents.

The threat of future prosecution and imprisonment would be used as a political weapon to sway the most sensitive and contentious Presidential decisions, diminishing the power, authority, and resolve of the Presidency.

Over 19 GOP-controlled states and more than two dozen Republican members of Congress support Trump's legal positions.

CONSTITUTIONAL CONCERNS

Some of the issues the court will have to consider:

Is it possible for a former president to be charged with "official acts" or do they have "complete immunity"?

The Supreme Court may limit or narrow "absolute immunity" in this case, as indicated by its official question framing that includes "whether and to what extent."

While court precedent may offer some protection to Trump from civil liability based on his official acts (Fitzgerald v. Nixon, 1982), he is still facing criminal charges brought by the government. The question now is whether the court will grant any implied civil protection to a criminal prosecution.

What is the difference between an official act of a president and a purely political or personal act by an incumbent candidate?

The federal appeals court that rejected Trump's arguments in a separate civil lawsuit alleging that he incited the violent Capitol mob with his "Stop the Steal" rally remarks on Jan. 6, 2021 concluded that "his campaign to win re-election is not an official presidential act." Trump is making the same immunity claims in those pending lawsuits.

In a separate 2020 case, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that the court recognizes absolute immunity for the President from damages resulting from official actions, but rejects absolute immunity from damages actions for nonofficial conduct.

The Clinton v. Jones case of 1997 established that a president cannot be immune from civil lawsuits for actions taken before assuming office and unrelated to their duties. The current legal battle centers on a criminal prosecution, and the justices must decide whether this warrants more consideration for the constitutional rights of both parties.

What acts are within the outer rim of a president's constitutional duties?

The high court now has the discretion to address the issue of presidential authority, as the lower federal courts avoided it. The justices may use questions or hypotheticals from the bench to explore the scope of presidential power when distinguishing between political and discretionary acts and duty-bound or ministerial acts.

In January, John Sauer, Trump's lawyer, argued before the DC-based federal appeals court that a president who orders Seal Team Six military commandos to assassinate a political rival could only be criminally prosecuted if first impeached by Congress.

The Supreme Court may compromise and issue a mixed ruling, rejecting Trump's broad immunity claims while preserving certain vital executive functions, such as the national security role of commander-in-chief. The uncertainty lies in how the justices will classify Trump's election-related conduct.

Can federal courts review a president's official discretionary decisions?

The 1952 Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer case, cited by Smith's team and others, established that a president's power to seize private property during a wartime emergency is limited without express congressional authorization. This landmark ruling, which restricted executive power, also confirmed the judiciary's duty to review a president's actions in office.

Will the Supreme Court ultimately decide not to decide and throw the competing issues back to the lower courts for further review?

If the justices experience buyer's remorse, they may decide that crucial questions were not adequately considered at the intermediate appellate or trial court level. This could lead to a significant delay in the trial.

If the trial proceeds, both sides will have the opportunity to present their arguments to a jury. After the verdict, the Supreme Court may reconsider the immunity issues.

Although Trump urged the court to address another issue, the court did not do so: whether the criminal prosecution violates the Fifth Amendment's ban on "double jeopardy," as he was acquitted by the Senate in February 2021 for election subversion, following his second impeachment.

NEXT STEPS

Trump is facing criminal charges in three different jurisdictions. He is being investigated for mishandling classified documents while in office, election interference in Georgia's 2020 voting procedures, and fraud in a New York case involving hush money payments to an adult film star in 2016.

Jury selection in the New York case began on April 15.

The start of the election interference trial in Washington is uncertain. The court's decision may delay proceedings until later this summer, early fall, or even much later.

If Trump wins re-election, he may order his attorney general to dismiss the Special Counsel and all his cases. Neither side's legal team has yet to publicly speculate on this scenario.

So, Jack Smith's case is frozen for now.

The Court is expediting the appeal decision, which would typically be made at the end of the term in late June, so a ruling could come sooner.

If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the government, the trial court will resume all discovery and pre-trial activities that were previously paused.

Trump's team would likely argue for at least several months before being ready for a jury trial, according to their team's argument to trial Judge Tanya Chutkan.

In December, Chutkan stated that she lacked jurisdiction over the matter since it was still pending before the Supreme Court, and she therefore halted the case against him until the justices made a decision on the merits.

If the former president wins a sweeping constitutional victory, his election interference prosecution is likely to collapse, and it could also affect his other pending criminal and civil cases.

Even if Trump loses before the Supreme Court, he may have gained a temporary victory, delaying any trial beyond Election Day on Nov. 5.

politics

You might also like

- California enclave announces it will cooperate with immigration officials and the Trump administration.

- Danish lawmaker urges Trump to abandon Greenland acquisition plan.

- Now, the Dem who labeled Trump an "existential threat to democracy" is obstructing his nominees.

- The lawyer for Hegseth criticizes the "dubious and inaccurate" testimony of his ex-sister-in-law.

- The House GOP outlines a plan to improve the healthcare system, emphasizing its impact on national defense.